The I Ching, or Book of Changes, is one of the oldest and most influential texts in Chinese philosophy, divination, and cosmology, with origins dating back thousands of years. It has evolved through various dynasties and philosophical traditions, shaping Chinese thought and practices like Feng Shui and traditional Chinese medicine[i].

This article provides an overview of its history, key discoveries (for example, Four Images, Early and Late Heaven Eight TrigramsHTBQ là một đồ hình Bát quái của Kinh Dịch. HTBQ phối với Lạc Thư. HTBQ or Late Heaven Eight Trigrams is I Ching's 8... More, He Tu, Luo Shu, King Wen’s 64 Hexagrams), and foundational concepts, including its cosmological framework and the Ten Wings, offering context for its comparison with the Circle-Square Dao.

Contents

- 1 Origins and Early Development

- 2 Foundational Diagrams and Concepts

- 3 Relationship Between Diagrams: Early Heaven, Late Heaven, He Tu, and Luo Shu

- 4 Earliest Documentation and First Appearance in Printing

- 5 The Ten Wings and Confucian Influence

- 6 I Ching Cosmology: From Taiji to Hexagrams

- 7 The Main Laws Of Change As Taught By The I Ching

- 8 Yin Yang And 5 Elements Theories

- 9 Distinct Origins and Early Purposes

- 10 The Process of Integration

- 11 Later Developments: Mai Hoa Dịch Số and Modern Influence

- 12 Conclusion

Origins and Early Development

The I Ching is believed to have originated during the Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BCE), though its roots may extend into antiquity. According to legend, the mythical emperor Fu Xi[ii] (c. 2800 BCE) discovered the Eight Trigrams (Ba Gua) by observing patterns in nature, particularly markings on a tortoise shell, laying the foundation for the I Ching’s hexagrams. Later, King Wen of Zhou (c. 11th century BCE) added the Hexagram judgments that provides insight into its meaning, reorganized the trigrams into the Later Heaven Arrangement, refining their use for divination and cosmology. His son, King Wu, and scholars like Gong Dan further developed the text, enriching its philosophical interpretations. The I Ching’s core – comprising the 64 hexagrams – was traditionally formalized during this period, with line statements, that elaborate on its significance within the hexagram, possibly added by the Duke of Zhou, though oral traditions likely predate these written records[iii].

Foundational Diagrams and Concepts

The I Ching’s cosmological framework relies on several ancient components, including the Solid-Yang and Broken-Yin Line, Four Images, Early and Late Heaven Eight TrigramsHTBQ là một đồ hình Bát quái của Kinh Dịch. HTBQ phối với Lạc Thư. HTBQ or Late Heaven Eight Trigrams is I Ching's 8... More, He Tu, Luo Shu, and King Wen’s 64 Hexagrams. These concepts, rooted in prehistoric myths and early Chinese philosophy, predate printed texts by centuries, with origins often tied to Neolithic observations of natural cycles (c. 5000–3000 BCE)[iv].

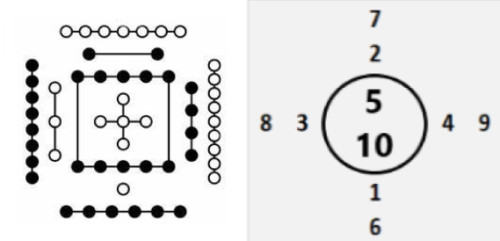

– He Tu (Yellow River Chart): This cosmological diagram encode numerology and trigram relationships. The He Tu, a 5×5 grid of numbers (1–10), is associated with the Early Heaven trigrams and the Five Elements, symbolizing static cosmic order. Legends claim it appeared on a dragon-horse during Fu Xi’s reign (c. 21st century BCE).

– Early Heaven Eight TrigramsTTBQ là Bát Quái của Kinh Dịch. TTBQ giống BQLD về vị trí các Quái, tuy nhiên, nó phối với Hà Đồ của KD, còn... More (Xiantian Bagua): The eight trigrams (Ba Gua), three-line figures representing natural forces (for example, Qian ☰ for Heaven, Kun ☷ for Earth), are central to the I Ching. The Early Heaven (Xiantian) arrangement, attributed to Fu Xi, reflects a static, primordial cosmic order with perfect balance and symmetry, emphasizing an idealized harmony.

These arrangements, possibly inspired by Neolithic patterns, were formalized in Zhou-era texts like the Shuo Gua (Discussion of the Trigrams), part of the Ten Wings. Archaeological evidence, such as numerical patterns from the Yangshao and Dawenkou cultures (c. 5000–3000 BCE), suggests prehistoric origins, though textual references appear later, in works like the Guanzi (c. 4th century BCE) and Han dynasty apocrypha.

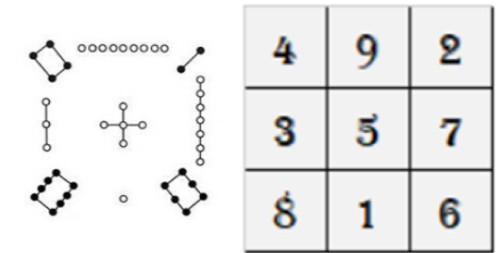

– The Luo Shu (Luo River Writing), a 3×3 magic square (numbers 1–9 summing to 15 in all directions), is tied to the Late Heaven sequence, quantifying dynamic change. It is said to have emerged on a turtle during Yu the Great’s reign (c. 21st century BCE).

– The Late Heaven Eight TrigramsHTBQ là một đồ hình Bát quái của Kinh Dịch. HTBQ phối với Lạc Thư. HTBQ or Late Heaven Eight Trigrams is I Ching's 8... More (Houtian Bagua) arrangement, attributed to King Wen (c. 11th century BCE), captures dynamic cycles suited to human affairs, such as seasons and directions, reflecting a cosmos in motion.

– Four Images[v] (Si Xiang): Emerging from the division of Taiji (Supreme Ultimate) into yin and yang, the Four Images – Greater Yang, Lesser Yin, Lesser Yang, and Greater Yin – represent stages of change. They symbolize the progression from primal duality to more complex states, foundational to the I Ching’s cosmology. Their conceptual roots likely trace to Neolithic times, but they are first explicitly discussed in the Xi Ci (Appended Statements) of the Ten Wings, compiled around the late Zhou Dynasty (c. 4th–3rd century BCE).

– King Wen’s 64 Hexagrams: The 64 hexagrams, each composed of two trigrams (six lines total), form the I Ching’s core, attributed to King Wen. Representing all possible combinations of yin and yang lines, they are used for divination and philosophical inquiry. Their structure and sequence likely evolved during the early Zhou Dynasty (c. 11th century BCE), with oral traditions possibly predating this. The Mawangdui Silk Texts (c. 168 BCE) confirm their standardization by the early Han Dynasty, though a different sequence in these texts indicates fluidity in early traditions[vi].

Relationship Between Diagrams: Early Heaven, Late Heaven, He Tu, and Luo Shu

The Early and Late Heaven arrangements, along with their associated diagrams (He Tu and Luo Shu), reflect distinct aspects of Chinese cosmology, bridging static order and dynamic change.

– Early Heaven and He Tu: The Early Heaven arrangement (on Figure 94: Early Heaven Eight TrigramsTTBQ là Bát Quái của Kinh Dịch. TTBQ giống BQLD về vị trí các Quái, tuy nhiên, nó phối với Hà Đồ của KD, còn... More) represents a primordial, static harmony where opposites are perfectly balanced, an archetype of cosmic perfection before dynamic change107. The He Tu, associated with the Early Heaven trigrams, symbolizes this static order through numerical patterns linked to the Five Elements. Often tied to the Yellow River in myth, it reflects nature’s ordering principles in an eternal state, though it plays a limited role in divination compared to the Late Heaven arrangement.

– Late Heaven and Luo Shu: The Late Heaven arrangement (on Figure 96: The Late Heaven Eight TrigramsHTBQ là một đồ hình Bát quái của Kinh Dịch. HTBQ phối với Lạc Thư. HTBQ or Late Heaven Eight Trigrams is I Ching's 8... More), designed for a world in flux, reinterprets the trigrams to mirror natural and human transformations, such as seasonal cycles[vii]. The Luo Shu, a 3×3 magic square, quantifies these dynamics, providing numerical grounding for the trigrams’ qualitative shifts. It bridges the trigrams to the 64 hexagrams by assigning numerical properties, supporting the combinatorial logic of 8 trigrams yielding 8 × 8 (64) configurations. The integration of Luo Shu numbers with Late Heaven enriches the I Ching’s ability to capture change, making it a cornerstone for divination and practical applications like Feng Shui.

– Yin-Yang Dynamics: The Late Heaven arrangement adjusts the yin-yang classifications of four trigrams to reflect their functional roles in a changing cosmos. For example, Li (Fire, ☲) and Dui (Lake, ☱) shift from Yang in Early Heaven to Yin in Late Heaven, emphasizing receptivity and inner illumination, while Kan (Water, ☵) and Gen (Mountain, ☶) transition from Yin to Yang, highlighting active transformation and assertiveness.

These shifts, as noted by scholars like Richard Wilhelm in his translation of the I Ching (Wilhelm, 1950), are not arbitrary but reflect a deep understanding of interdependent forces. Joseph Needham, in his work on Chinese science, underscores that these adjustments adapt the cosmological schema to human and natural dynamics (Needham, 1956). Zhu Xi’s《周易本义》 (Zhou Yi Ben Yi, “Original Meaning of the Zhou Yi”) interprets the trigrams’ Yin-Yang nature through the lens of functional activity (用, yòng) rather than static form (体, tǐ). For instance, ☲ Li (Fire), though structurally Yang (solid lines dominate), is functionally Yin in Later Heaven because its hollow center (broken Yin line) symbolizes dependence and receptivity; and ☵ Kan (Water), though structurally Yin (broken lines dominate), is functionally Yang due to its relentless movement. In《皇极经世》 (Huángjí Jīngshì, “Cosmic Chronology”) by Shao Yong (邵雍) explains that the Early Heaven arrangement represents ideal balance (Heaven-Earth polarity), while Later Heaven reflects temporal interactions (for example, seasonal cycles). For example: ☱ Dui (Lake) shifts from Yang to Yin because its joyful, expansive nature (Yang) is tempered by its yielding surface (Yin) in earthly contexts.

Despite these shifts, the trigrams’ element type – for example, Qian as Metal, Li as Fire, Kan as Water – remain constant, rooted in the Five Elements (Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal, Water).

Earliest Documentation and First Appearance in Printing

These concepts predate printing, initially appearing in manuscripts or oral traditions, and were later codified in printed texts as printing technology developed in China.

– Earliest Documentation (Pre-Printing):

- Four Images: Mentioned in the Xi Ci (Ten Wings), compiled by the late Zhou Dynasty (c. 4th–3rd century BCE), describing their role in the progression from Taiji to hexagrams.

- Early and Late Heaven Trigrams: The Shuo Gua (Ten Wings) contrasts these arrangements, attributing them to Fu Xi and King Wen, dating to the late Zhou Dynasty. The Guming chapter of the Shangshu (Book of Documents, c. 5th–4th century BCE) references the He Tu, implying early knowledge of trigram-related diagrams.

- He Tu and Luo Shu: The Guanzi (c. 4th century BCE) mentions the Luo Shu, and Han Dynasty scholars like Kong Anguo linked the He Tu to a dragon-horse legend in Shangshu commentaries. Archaeological finds, like the Fuyang divination dish (Warring States, c. 5th–3rd century BCE), show numerical patterns akin to these diagrams.

- King Wen’s 64 Hexagrams: The I Ching’s core text, including hexagram names and judgments, dates to King Wen (c. 11th century BCE), with line statements possibly added by the Duke of Zhou. The Mawangdui Silk Texts (c. 168 BCE) confirm their early standardization.

– First Appearance in Printing:

Printing began in China during the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE), becoming widespread by the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE). The I Ching and its related concepts were among the earliest printed texts due to their cultural significance:

- I Ching and Ten Wings (Including Four Images, Trigrams, Hexagrams): The earliest known printed I Ching dates to the Song Dynasty, around 990 CE, as part of the Seven Classics editions under imperial patronage. The Ten Wings, including the Xi Ci and Shuo Gua, were printed alongside, codifying these concepts.

- He Tu and Luo Shu: These diagrams appeared in Song Dynasty I Ching commentaries and Neo-Confucian texts, such as the Zhouyi Tushu (c. 11th–12th century CE), influenced by scholars like Zhu Xi (1130–1200 CE). Earlier Han weft texts (chenwei) were likely copied in manuscripts, but printing began in the Song.

- King Wen’s 64 Hexagrams: Printed as part of the I Ching by 990 CE in Song editions, with the King Wen sequence dominating.

– Timeline Summary:

- Pre-Zhou (Neolithic, c. 5000–2000 BCE): Possible oral/material origins of He Tu/Luo Shu-like patterns.

- Zhou Dynasty (c. 11th–3rd century BCE): Hexagrams (King Wen), trigrams, and Four Images formalized.

- Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE): Ten Wings compiled; He Tu and Luo Shu documented.

- Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE): First printing of I Ching with Ten Wings (c. 990 CE); He Tu and Luo Shu in cosmological texts (c. 1000–1100 CE).

The Ten Wings and Confucian Influence

During the Warring States period (5th–3rd century BCE), the I Ching was expanded with the Ten Wings (Shih Yi), a set of commentaries traditionally attributed to Confucius or his disciples. Officially recognized as part of the I Ching by 136 BCE, the Ten Wings elevated its status as a classical text, linking it to Confucian thought[viii]. They include:

1. Tuan Zhuan (Commentary on the Decision, two parts): Explains hexagram judgments and moral implications.

2. Xiang Zhuan (Commentary on the Images, two parts): Interprets hexagram symbolism.

3. Wen Yan (Commentary on the Words): Focuses on Qian (Heaven) and Kun (Earth), exploring their significance.

4. Xi Ci (Appended Statements, two parts): Discusses the philosophy of change and cosmology.

5. Shuo Gua (Discussion of the Trigrams): Analyzes the eight trigrams’ attributes.

6. Xu Gua (Sequence of Hexagrams): Explains the hexagram order.

7. Za Gua (Miscellaneous Notes): Provides additional insights[ix].

The Ten Wings, particularly the Xi Ci, elaborate on the I Ching’s cosmology, describing the Tao as the source of all things, manifesting through yin and yang: “One yin and one yang constitute what is called the Tao.” This process of polarity and balance drives creation, guiding individuals to act in harmony with the natural order. The Tuan Zhuan and Wen Yan highlight Qian (creativity) and Kun (receptivity) as dual aspects of the Tao, while the Shuo Gua links trigrams to natural phenomena, and the Xi Ci connects the Tao to human affairs, emphasizing virtues like humility and sincerity.

I Ching Cosmology: From Taiji to Hexagrams

The I Ching’s cosmology, detailed in the Xi Ci, outlines a progression from the unmanifested to the manifested:

1. Taiji (Supreme Ultimate): The undifferentiated unity, the source of existence.

2. Yin and Yang: Taiji divides into two primal forces – yin (broken line, –) and yang (solid line, – ).

3. Four Images (Si Xiang): Yin and yang form four two-line figures (Greater Yang, Lesser Yin, Lesser Yang, Greater Yin).

4. Eight Trigrams (Bagua): Adding a third line produces the eight trigrams, representing natural patterns.

5. 64 Hexagrams: Combining trigrams pairwise yields 64 six-line figures, encompassing all transformations.

This sequence reflects a movement from simplicity to complexity, guiding the I Ching’s use in understanding change and harmony in the universe.

The Main Laws Of Change As Taught By The I Ching

Below, we’ll explore some key laws of the I Ching[x]:

1. The Principle of Change

Constant Flux: The I Ching teaches that change is the fundamental nature of the universe. Everything is in a state of flux, and understanding this principle allows individuals to adapt to their circumstances effectively. The text emphasizes that change is not chaotic but follows certain patterns and cycles, which can be observed and understood.

By engaging with the text, individuals can gain insights into the dynamics of their current situations and how these may evolve over time. The act of consulting the I Ching is not about fixing things permanently but understanding their fluid nature.

2. Yin and Yang

Complementary Forces: The interaction between Yin (broken lines) and Yang (solid lines) is central to the I Ching’s philosophy. These two forces represent opposite yet complementary aspects of reality. Their dynamic interplay creates all phenomena, and recognizing their balance is crucial for achieving harmony in life.

3. Interconnectedness

Holistic Perspective: The I Ching teaches that all things are interconnected. Each hexagram represents a specific state of change influenced by various factors. Understanding these connections allows individuals to see how their actions can impact broader circumstances, promoting mindfulness in decision-making.

4. Dynamic Balance

Equilibrium in Motion: True balance is dynamic rather than static. The I Ching emphasizes that life involves continuous adjustments as circumstances evolve. Each hexagram reflects a specific state of change, guiding individuals on how to respond appropriately to maintain equilibrium.

5. Cycles of Change

Natural Rhythms: The I Ching highlights the cyclical nature of existence, where situations can transform into their opposites over time. For example, after a period of growth (Yang), there may be a phase of decline (Yin). Recognizing these cycles helps individuals prepare for transitions and align their actions with natural rhythms.

6. Practical Wisdom

Guidance for Action: The I Ching serves as a practical guide for decision-making. Through divination methods – such as casting coins or yarrow sticks – individuals can consult the text for insights relevant to their specific situations. Each hexagram offers advice on how to approach challenges and opportunities based on the current state of change.

7. Moral Guidance

Ethical Considerations: The teachings of the I Ching include moral principles that emphasize virtues such as humility, patience, and respect for others. It encourages self-reflection and awareness of one’s actions in relation to others, promoting a balanced approach to life.

8. Outcomes of Change

Continuum of Fortune: According to the I Ching, every change leads to an outcome situated on a continuum between good fortune (ji) and misfortune (xiong). Understanding this continuum helps individuals navigate life’s uncertainties with greater awareness and adaptability.

Summary

The laws of change contained in the teachings of the I Ching provide a comprehensive framework for understanding the nature of reality and guiding personal conduct. By emphasizing principles such as Yin and Yang, interconnectedness, dynamic balance, and practical wisdom, the I Ching remains a timeless resource for navigating life’s complexities and achieving harmony with the natural world.

Yin Yang And 5 Elements Theories

The separation – and eventual interplay – of Yin–Yang theory and the Five Elements[xi] (Wu Xing) in Chinese thought reflects their distinct origins and the different aspects of reality they were designed to explain. Although both systems now coexist in many Chinese cosmological frameworks, their initial development and subsequent integration followed unique paths. Below is an exploration of why these theories were originally separate, how they later merged, and why Taoism does not fully subsume the Five Elements into its use of the I Ching.

Distinct Origins and Early Purposes

Yin–Yang Theory:

Yin and Yang emerged as a way to understand the natural world in terms of dualities. Early Chinese observers noted that the world is filled with opposing yet complementary forces – light and dark, active and passive, hard and soft. This binary framework was initially used to explain day and night, the shifting of the seasons, and the natural cycles seen in everyday life. Yin–Yang is primarily qualitative, addressing the relational qualities of phenomena, promoting a dynamic balance between opposites. In early Chinese philosophy, it was a lens to view transformation and interdependence rather than a rigid categorization of matter.

Five Elements (Wu Xing) Theory:

In contrast, the Five Elements theory evolved from material observation. It classifies the basic ingredients or phases of the material world into five categories: Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal, and Water. Each element represents a type of energy or process observed in nature – for instance, the growth (Wood), the transformation (Fire), stability (Earth), contraction (Metal), and flow (Water). Unlike Yin–Yang, which divides the world into a dualistic framework, the Five Elements theory offers a more systematic and sequential ordering of natural processes. Originally, these two conceptual systems addressed different questions: Yin–Yang explained the “how” in the natural interplay (the process of change), while the Five Elements described “what” the substance of change was.

According to scholars discussing Chinese philosophy, such as those detailed on platforms that explore classical Chinese cosmology , these models were developed independently to interpret different layers of reality. Yin–Yang captured the dynamism and fluid polarity of all matter, whereas the Five Elements provided a taxonomy of natural phenomena based on seasonal cycles, growth, and decay.

The Process of Integration

Over time, as Chinese thought became more systematized, intellectual traditions began drawing connections between these two frameworks. The gradual merging wasn’t an abandonment of their distinctive roles but rather an effort to create a comprehensive cosmological model that could explain both the qualitative and quantitative aspects of nature.

Integration in Cosmology and Medicine:

By the late Warring States and early Han periods, scholars and practitioners – especially in medicine, feng shui, and astrology – began to employ both systems concurrently. In traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), for example, the balancing of Yin and Yang is understood alongside the interactions and cycles of the Five Elements. TCM practitioners use Yin–Yang theory to diagnose the overall energy balance of a patient, while the Five Elements help explain the physiological processes and inter-relationships between organs. This dual application allowed for a multidimensional analysis of health and disease, integrating change (Yin–Yang) with material substance (Five Elements).

Similarly, in feng shui, environmental features are not only assessed for their yin or yang characteristics but are also categorized by elemental attributes. This synthesis makes it possible to design living spaces that honor both energetic flow and elemental harmony.

Philosophical Synthesis:

Nonetheless, the two systems retained their distinct identities even as they became interrelated. Yin–Yang continued to serve as the overarching principle describing the interplay of forces, while the Five Elements provided the “grammar” of material transformation. The later synthesis did not erase their individual logics; rather, it enriched the analytical possibilities of Chinese cosmology by linking dynamic processes with stable categorical properties. The interplay between these models helps explain not only how things change but also what they are fundamentally composed of.

Later Developments: Mai Hoa Dịch Số and Modern Influence

The I Ching continued to evolve through later dynasties. In 136 BCE, Emperor Wu declares the I Ching one of the Five Classics, leading to its standardization among competing versions. This solidifies its status as a central text in Confucian thought. In the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE), it gained widespread scholarly attention through extensive commentaries, including those by prominent scholars like Wang Bi, who provide new interpretations and insights into the text.

In the Song Dynasty, Shao Yong (1011–1077 CE), a Neo-Confucian scholar, developed Mai Hoa Dịch Số (Plum Blossom Numerology), a divination method using trigrams and hexagrams derived from environmental observations (for example, numbers, sounds), printed in texts by the 12th–13th century CE. This method built on the I Ching’s framework rather than introducing new concepts[xii]. In the modern era, the I Ching remains relevant for its philosophical, psychological, and divinatory applications, influencing fields beyond traditional Chinese thought.

The I Ching gains attention in Western philosophy and psychology, particularly through figures like Carl Jung, who explore its applications in understanding human psychology and decision-making. Numerous translations and interpretations like of Richard Wilhelm emerge, adapting the text for contemporary audiences while attempting to preserve its original meanings.

Conclusion

The I Ching’s development spans millennia, from its origins in the Zhou Dynasty to its codification in the Han and printing in the Song (c. 990–1100 CE). Key concepts like the Yin Yang, Five Elements, Four Images, Early and Late Heaven Trigrams, He Tu, Luo Shu, and King Wen’s 64 Hexagrams, rooted in ancient traditions, provide a framework for understanding cosmic order and change. The Ten Wings enriched its philosophical depth, linking it to Confucian ethics and cosmology. Together, these elements make the I Ching a timeless guide, bridging static harmony (Early Heaven, He Tu) and dynamic transformation (Late Heaven, Luo Shu).

[i] I Ching. Source URL.

[ii] “Fu Xi is too far away for us to see him clearly. Let us agree that we are looking through layers of myth, legend, historical fact, and philosophical ideas”. Deng Ming-Dao. THE LIVING I CHING: Using Ancient Chinese Wisdom to Shape Your Life. HarperCollins, 2006.

[iii] According to myth, Fu Xi, around 12,000 BC, invented the Bagua, using numbers or images he saw on tortoise shells. The addition of texts and inscriptions attributed to King Wen and/or the Duke of Zhou would date the texts to around 1046, the transition period from the Shang to the Zhou. This date is widely accepted in traditional China, but recent scholars have found no evidence of the role of these cultural heroes and have pushed the estimated compilation date earlier. Geoffrey Redmond. The I Ching (Book of Changes). Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2017.

[iv] We must set aside the myth of the lone sage or genius and recognize that the I Ching (and similar texts) are collective, layered works. They were compiled from diverse, now-unknown sources over time, not authored or edited in the modern sense. This makes it difficult to analyze their origins or attribute them to specific individuals, and it complicates efforts to distinguish original material from later additions. Geoffrey Redmond. The I Ching (Book of Changes). Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2017.

[v] Deng Ming-Dao. THE LIVING I CHING: Using Ancient Chinese Wisdom to Shape Your Life. HarperCollins, 2006.

[vi] These are the titles or tags, the hexagram symbol, the judgment or hexagram texts, and line texts. Geoffrey Redmond. The I Ching (Book of Changes). Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2017.

[vii] Decoding Early Heaven and Later Heaven Bagua. Source URL.

[viii] The Ten Wings: A Deeper Understanding of the I Ching. Source URL.

[ix] The later commentaries, added centuries after the original text, reinterpret the Zhouyi’s simple metaphors and practical advice, infusing them with Confucian, Daoist, and broader cosmological significance. The Ten Wings systematize and expand the text’s meaning, turning it into a source of moral and metaphysical wisdom and making it suitable for philosophical reflection and ethical instruction. The philosophical inspirations of the Da Zhuan in interpreting the Zhouyi (Yijing).

[x] The original Zhouyi is not a systematic spiritual or philosophical treatise. Its primary content is practical, offering metaphorical guidance for specific situations-such as whether it is a good time to undertake a journey or meet a powerful person. It does not present general principles for living, as seen in the Dao De Jing or the Analects (Lunyu). Any wisdom it contains is scattered, often in the form of proverbs, and not organized into a coherent philosophy. The text only became an ethical, spiritual, and philosophical classic after the addition of the Ten Wings (especially the Dazhuan or Great Commentary). Geoffrey Redmond. The I Ching (Book of Changes). Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2017.

[xi] Russell Kirkland: The I Ching, Yin-Yang, And The “Five Forces”. Source URL.

[xii] Mai Hoa Dịch số. Source URL.